Portugal – The Pioneer of Globalization

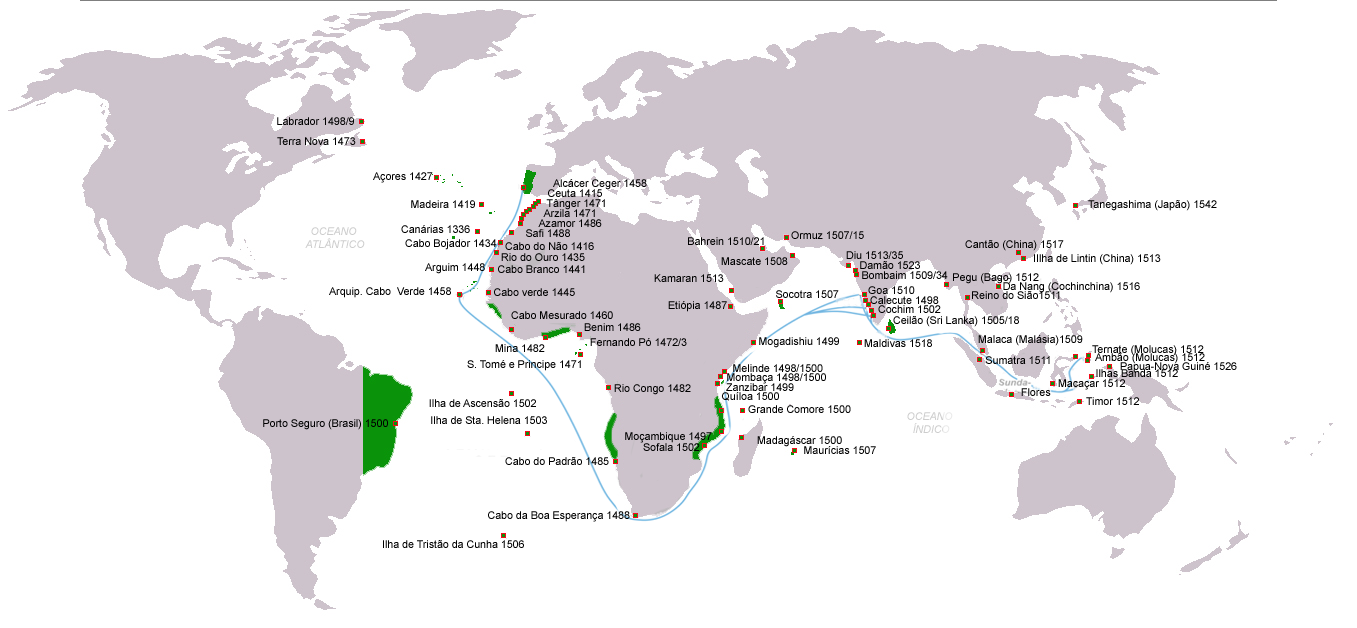

Want to know how big was the Portuguese Empire, that started more than 500 years ago? Check the map and be surprised to see where the Portuguese were sailing!

Europe’s exploration of the world begins in the 15th century, pioneered by Portugal. The Portuguese sailors are under the control of Henry, one of the sons of John I. Although no seaman himself, his energy and vision earns him the name by which history knows him – Prince Henry the Navigator.

In 1415 the Portuguese sail a fleet of some 200 ships from Lisbon to attack the Muslims on the African coast. They successfully take the strategic promontory of Ceuta, on the southern side of the Straits of Gibraltar. The 21-year-old Henry is one of the first to fight his way into the city. He is subsequently given responsibility for the Portuguese garrison there.

The capture of Ceuta seems to be the event which fires Henry’s enthusiasm for exploration round Africa’s coasts. Later in his life he builds himself a villa at Sagres, in the extreme southwest of Portugal, where he establishes a laboratory of seafaring. He gathers there a team of skilled navigators, geographers and mapmakers. His ships sail from the Portuguese harbour of Lagos, a few miles to the east.

The main purpose of Prince Henry‘s efforts will be expeditions pressing ever further south round Africa. But his attention is first drawn to island groups in the Atlantic – Madeira and the Azores.

Madeira features on an Italian portolan chart of 1351 but an accidental sighting by a Portuguese navigator, blown off course in 1418, is regarded at the time as a discovery. Returning in 1420, the navigator (João Gonçalves Zarco) finds the island uninhabited and lush. Prince Henry immediately despatches colonists both for Madeira and its smaller companion, Porto Santo. The forests are slashed and burned. Rich land is brought into cultivation, mainly for sugar cane and vineyards.

The productivity of the islands soon comes to depend on another aspect of Portugal’s new seafaring activities – the African slave trade, which results from Prince Henry‘s later expeditions.

A group of islands much further into the ocean is sighted by a Portuguese ship in 1427. Prince Henry sends settlers to the Azores from 1432.

The practical use of these islands is not yet obvious. But with the European discovery of America in 1492, and of the sea route round Africa to India in 1498, the Azores become an invaluable landfall almost in the middle of the north Atlantic. They are particularly well placed, in later centuries, for ships on the long curving ocean route between Europe and the Cape of Good Hope. As yet these future advantages are unknown to Henry the Navigator, whose ambitions now centre on Africa.

Down the African coast: 1434-1460

Many and varied motives lie behind Prince Henry’s African expeditions. In part they are pure voyages of discovery, driven by a longing to know what new places, people, animals or plants may lie beyond the next forbidding headland. Partly they are a straightforward quest for Africa’s gold. Then there is the hope of colonizing new lands for Portugal. There is the desire to spread Christianity and frustrate Islam. There is even the fanciful dream of coming across a fabulous Christian ruler, Prester John.

But the overriding purpose is to discover a sea route round Africa to the east, with its rich promise of trade in valuable spices.

Ocean-going ships are improving at this period (the era of the caravel), but the sheer difficulty faced by the sailors is well suggested by the long struggle to get round Cape Bojador – a promontory only about 150 miles south of the Canaries. Prince Henry sends out fourteen expeditions to attempt this feat before at last one is successful, in 1434.

In the 1440s progress is quicker. Caravels sail round Cape Verde in 1444 and Cape Roxo in 1446, bringing them to the northern part of what is later Portuguese Guinea. By the time of Prince Henry’s death, in 1460, navigators have explored as far south as Sierra Leone. They have also discovered the uninhabited Cape Verde islands.

Portuguese settlers move into the Cape Verde islands in about 1460. In 1466 they are given an economic advantage which guarantees their prosperity. They are granted a monopoly of a new slave trade. On the coast of Guinea the Portuguese are now setting up trading stations to buy captive Africans.

Some of these slaves are used to work the settlers’ estates in the Cape Verde islands. Others are sent north for sale in Madeira, or in Portugal and Spain – where Seville now becomes an important market. Africans have been imported by this sea route into Europe since at least 1444, when one of Henry the Navigator’s expeditions returns with slaves exchanged for Moorish prisoners.

Dias and the Cape of Good Hope: 1487-1488

The two most significant Portuguese voyages of exploration take place a generation after the death of Henry the Navigator. In the first, in 1487-8, Bartolomeu Dias proves that there is a sea route round the southern tip of Africa. In the second, ten years later, Vasco da Gama demonstrates that this route leads to India.

Dias is already a veteran navigator along the coast of northwest Africa when he sets off from Lisbon, in August 1487, with two caravels and a storeship. Two or three months later he passes Cape Cross – reached in the previous year by Diogo Cam, and as yet the furthest point south of any Portuguese expedition.

Dias abandons his depleted store ship somewhere south of Cape Cross. At Angra Pequena he pauses to erect a stone pillar, declaring that the king of Portugal is the overlord of this region. These pillars, and this claim, have by now become the standard practice of the Portuguese expeditions whenever new territory is reached. Diogo Cam, the immediate predecessor of Dias, has erected four – at the mouth of the Congo, at Cape Santa Maria, at Cape Negro and Cape Cross.

From Angra Pequena the two caravels of Dias sail due south. They see no land for thirteen days. Dias turns northeast.

He makes landfall at Mossel Bay in February 1488. The coastline here runs east and west. Dias, whose crew are becoming restless, continues to the east. At Cape Padrone, where he sets up a second pillar, his officers insist that they have achieved enough. They should set sail for Portugal. He persuades them to continue a little further until the northeast trend of the coastline becomes unmistakable. This seems indeed to be the case by the time they have reached the Great Fish river. The two ships turn home.

On the way back Dias erects a third stone pillar at the Cape of Good Hope – a magnificent acquisition for the king of Portugal, previously missed because of the long seaward loop on the journey out.

Dias and his ships reach Lisbon in December 1488. They have been away for sixteen months. They have sailed round more than 1200 miles of previously undiscovered coastline. They have not reached India, but their rounding of the Cape is considered proof that this longer journey is possible.

When the next major attempt is planned, Dias is put in charge of building the two main caravels. But the command of the expedition is given to a younger man, Vasco da Gama. The ships leave Lisbon in 1497. Dias is allowed to accompany them, but only as far as the Cape Verde Islands – a mere hop for a navigator of his distinction.

The Tordesillas Line: 1493-1500

When Columbus returns to Spain in 1493, with the first news of the West Indies, Ferdinand and Isabella are determined to ensure that these valuable discoveries belong to them rather than to seafaring Portugal. They secure from the Borgia pope, Alexander VI, a papal bull to the effect that all lands west of a certain line shall belong exclusively to Spain (in return for converting the heathen). All those to the east of the line shall belong on the same basis to Portugal.

The pope draws this line down through the Atlantic 100 leagues (300 miles) west of the Cape Verde islands, Portugal’s most westerly possession.

The king of Portugal, John II, protests that this trims him too tight. The line cramps the route which Portuguese sailors must take through the Atlantic before turning east round Africa.

Spanish and Portuguese ambassadors, meeting in 1494 at Tordesillas in northwest Spain, resolve the dispute. They accept the principle of the line but agree to move it to a point 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands. The new line has a profound significance which no one as yet appreciates. It slices through the entire eastern part of south America from the mouth of the Amazon to São Paulo.

The east coast of south America is first reached by Spanish and Portuguese navigators in the same year, 1500. The agreement at Tordesillas gives the territory to Portugal.

Thus the vast area of Brazil, the largest territory of south America, becomes an exception in the subcontinent – the only part not to be in the Spanish empire, and the only modern country in Latin America with Portuguese rather than Spanish as its national language.

The Portuguese and India: 1497-1502

An important expedition to the east leaves Lisbon in 1497. In July Vasco da Gama sails south in his flagship, the St Gabriel, accompanied by three other vessels. In late November the little fleet rounds the Cape of Good Hope. Soon they are further up the east coast of Africa than Dias ventured ten years earler. In March they reach Mozambique. They are excited to find Arab vessels in the harbour, trading in gold, silver and spices, and to hear that Prester John is alive and well, living somewhere inland.

In the well-established Portuguese tradition, da Gama has on board a good supply of stone pillars. He sets one up in each new territory, to claim it for his king.

The real prize lies ahead, a dangerous journey away, across the Indian Ocean. At Malindi, on the coast of Kenya, a pilot is found who knows the route northeast to Calicut, an important trading centre in southern India.

After twenty-three days Calicut is safely reached. Da Gama is welcomed by the local Hindu ruler, who must surely wonder why his guest is so keen to erect a stone pillar.

Da Gama spends three months in Calicut before sailing back to Africa. Adverse winds extend the crossing this time from three weeks to three months, and before the African coast is reached many of the crew die of scurvy — a first glimpse of one of the problems of ocean travel.

Da Gama arrives back in Lisbon in September 1499, more than two years after his departure. He is richly rewarded by the king, Manuel I, with honours, money and land. He has not managed to conclude a treaty with the ruler of Calicut. But he has proved that trade with the east by sea is possible. Manuel moves quickly to seize the opportunity.

Six months later, in March 1500, the king sends Pedro Cabral on the same journey. He takes such a curving westerly route through the Atlantic that he chances upon the coast of Brazil (an accident with its own significant results). This time a warehouse is established in Calicut, but the Portuguese left there to run it are murdered. To avenge this act, da Gama is sent east again in 1502. He bombards Calicut from mortars aboard his ship. With this clear evidence of Portuguese power a treaty becomes available.

These events, east and west in India and Brazil, provide the basis of the Portuguese empire, with all its rich opportunities for future traders and missionaries.

The profitable trade in eastern spices is cornered by the Portuguese in the 16th century to the detriment of Venice, which has previously had a virtual monopoly of these valuable commodities – until now brought overland through India and Arabia, and then across the Mediterranean by the Venetians for distribution in western Europe.

By establishing the sea route round the Cape, Portugal can undercut the Venetian trade with its profusion of middlemen. The new route is firmly secured for Portugal by the activities of Afonso de Albuquerque, who takes up his duties as the Portuguese viceroy of India in 1508.

The early explorers up the east Africa coast have left Portugal with bases in Mozambique and Zanzibar. Albuquerque extends this secure route eastwards by capturing and fortifying Hormuz at the mouth of the Persian Gulf in 1514, Goa on the west coast of India in 1510 (where he massacres the entire Muslim population for the effrontery of resisting him) and Malacca, guarding the narrowest channel of the route east, in 1511.

The island of Bombay is ceded to the Portuguese in 1534. An early Portuguese presence in Sri Lanka is steadily increased during the century. And in 1557 Portuguese merchants establish a colony on the island of Macao. Goa functions from the start as the capital of Portuguese India.

With this chain of fortified ports of call, and with no vessels in the Indian Ocean capable of challenging her power at sea, Portugal has a monopoly of the eastern spice trade.

Indeed the English, now developing interests of their own in ocean commerce, consider that their only hope of trade with the far east is to find a route north of Russia. One of the first joint-stock enterprises, the Muscovy Company chartered in 1555, results from early efforts to find a northeast passage.

Of the other Atlantic maritime powers, Spain is mainly occupied with its American responsibilities. And the Dutch enjoy a direct benefit from Portugal’s trade. Their ships have a monopoly in ferrying the precious eastern cargoes from Lisbon to northern Europe.

The situation changes suddenly in 1580, when the Spanish (perennial enemies of the Dutch) occupy Portugal.

- admin

- on Nov, 26, 2014

- No Comments.

Comments are closed.